Mid-Decade Milestones in U.S.–Japan Baseball Relations (1875–2025)

A 150-Year Journey Through the Game That Bridges Nations

Ichiro Suzuki’s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on July 27, 2025 is a milestone worth celebrating—and an opportunity to reflect on the progress of U.S.–Japan baseball relations. From Ichiro’s enshrinement to the sandlot games played by Japanese school children during the 1870s, the history of baseball between the U.S. and Japan is a rich narrative of cultural exchange, perseverance, diplomacy, and innovation.

With that in mind, I thought it would be fun to use Ichiro’s 2025 achievement as a springboard to explore key mid-decade milestones (years ending in five) in the U.S.–Japan baseball journey. Let's look at how the sport evolved from a foreign curiosity into a shared national passion—and ultimately, a bridge between two nations.

Let’s begin in the present and work our way backward.

2025

Ichiro Suzuki was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2025, receiving 393 out of 394 votes (99.75%) in his first year on the ballot. This made him the first Japanese-born position player elected to Cooperstown, though he fell one vote shy of unanimous selection—a distinction held by Mariano Rivera in 2019. In anticipation of his enshrinement, the Hall of Fame created a new exhibit titled Yakyu | Baseball: The Transpacific Exchange of the Game. The exhibit will open in July 2025 and remain on display for at least five years. Learn more at: https://baseballhall.org/yakyu.

2015

Ichiro, now with the Miami Marlins, begins symbolically "passing the torch" to Shohei Ohtani, who is in the second year of his professional career with the Nippon Ham Fighters in Japan. The 2015 season marks Ichiro's first appearance as a pitcher, setting the stage for a rare and unexpected future Hall of Fame connection between Ichiro and Ohtani—two Japanese-born players who both pitched and hit a grand slam during their MLB careers. Ichiro hit just one grand slam, while Ohtani has hit three (as of this post), and intriguingly, all of them against the Tampa Bay Rays.

2005

Tadahito Iguchi becomes the first Japanese-born player to compete in and win a World Series, contributing to the Chicago White Sox’s historic run. (Note: Hideki Irabu received a World Series ring as a member of the 1998 and 1998 New York Yankees, but did not play in any postseason games). Check out Iguchi’s SABR Bio.

1995

Hideo Nomo joins the Los Angeles Dodgers, earning Rookie of the Year, an all-star game start, and igniting “Nomomania.” His success breaks open the modern pipeline between NPB and MLB and reshapes the perception of Japanese players on the global stage. Check out Nomo’s SABR Bio.

1985

Pete Rose breaks Ty Cobb’s all-time hit record using a Mizuno bat. After visiting Japan in 1978, Rose teamed up with sports agent Cappy Harada to sign a sponsorship deal with Mizuno in 1980. Rose’s partnership with Mizuno marked a significant moment in sports history, symbolizing Japan's growing influence in global sports and helping to establish Japanese manufacturers as credible names in American dugouts and MLB clubhouses.

1975

The Chunichi Dragons, led by manager Wally Yonamine, and the Yomiuri Giants, led by manager Shigeo Nagashima, conduct spring training in Florida. Meanwhile, American-born manager Joe Lutz and Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn contribute to Japanese baseball by joining the Hiroshima Carp. Lutz becomes the second U.S.-born manager in NPB history after WWII, following Hawaii-native Yonamine. However, Lutz’s time with the Carp is short-lived, as he steps down just weeks into the new season. Spahn continues his role with the Carp and states that he prefers working in Japan compared to the U.S.

1965

Masanori Murakami finishes his rookie season with the San Francisco Giants after debuting in 1964, becoming the first Japanese-born player in MLB. His success inspires generations of Japanese players to dream of American stardom.

1955

After a season in the minor leagues and facing lingering post–World War II anti-Japanese sentiment, California native Satoshi “Fibber” Hirayama chose to continue his professional baseball career in Japan, signing with the Hiroshima Carp. That same season, the New York Yankees toured Japan, and afterward, former Japanese pitching star and Hawai‘i native Bozo Wakabayashi was hired as a scout for the team. However, Yankees manager Casey Stengel resisted the idea of signing Japanese players, citing concerns about adding new talent to an already talent-heavy roster.

1945

In the aftermath of World War II, baseball became a source of healing and pride for Japanese Americans unjustly incarcerated behind barbed wire. At the Gila River camp in Arizona, the Butte High Eagles stunned the defending state champions, the Tucson High Badgers, with an 11–10 extra-innings victory. Coach Kenichi Zenimura called it “the greatest game ever played at Gila.” After graduating, Eagles second baseman Kenso Zenimura relocated to Chicago, where he attended the East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park and watched Kansas City Monarchs standout Jackie Robinson during his lone season in the Negro Leagues. Learn more about Zenimura Field.

1935

The founding of the Tokyo Giants paved the way for the launch of the Japanese Professional Baseball League in 1936. During the team’s groundbreaking U.S. tour, four players -- pitchers Victor Starffin and Eiji Sawamura, infielder Takeo Tabe, and outfielder Jimmy Horio -- attracted interest from American professional clubs and received contract offers. However, the 1924 Immigration Act rendered Japanese-born players ineligible to sign with U.S. teams. Only one player—Hawaii-born Horio—was eligible under U.S. law. He signed with the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League for the 1935 season but returned to Japan the following year to join the Hankyu Braves in the new professional league.

1925

Sponsored by the Osaka Mainichi newspaper, a semipro team called Daimai was formed and sent on tour in the United States, where they faced American universities and semi-pro clubs, including the Japanese American Fresno Athletic Club (FAC). In early September, the FAC played a doubleheader at White Sox Park in Los Angeles—the first game against Daimai, and the second against the L.A. White Sox, the premier Negro Leagues team in Southern California. Behind the strong pitching of Kenso Nushida, FAC edged out the White Sox 5–4, setting the stage for rematches in 1926 and parallel tours of Japan in 1927. White Sox manager Lon Goodwin rebranded his team as the Philadelphia Royal Giants for the Japan tour, ushering in a new era of international baseball exchange.

1915

The Hawaiian Travelers, a barnstorming team made up of Chinese and Japanese Americans from the Hawaiian Territories, toured the U.S. mainland in the early 20th century. Two Japanese players, Jimmy Moriyama and Andy Yamashiro, joined the team under assumed Chinese identities, playing as “Chin” and “Yim.” The Travelers impressed fans and opponents alike with victories over top Negro League clubs such as the Lincoln Giants and Brooklyn Royal Giants—both teams now deignated as major league caliber by SABR. After a return tour, Yamashiro, still using the name Andy Yim, signed with the Gettysburg Ponies of the Class D Blue Ridge League in 1917, quietly becoming the first Japanese American to join an integrated professional team—though history recorded him only under his adopted identity. Meanwhile, an Osaka newspaper, Asahi Shinbun, sponsors a national tournament for high school teams that eventually becomes one of the most popular sporting events in Japan (known today as the Koshien Tournament).

1905

The 1905 Waseda University baseball tour was the first time a Japanese college team traveled to the United States to compete, playing 26 games along the West Coast and finishing with a record of 7 wins and 19 losses. The team was led by Abe Isō, a Waseda professor, Unitarian minister, and politician who saw baseball as a powerful tool for international exchange and cultural diplomacy. Although Waseda struggled on the field, the tour was a landmark moment in U.S.–Japan relations, helping to lay the groundwork for future athletic and cultural connections between the two nations. Meanwhile, John McGraw of the New York Giants gave a tryout to a Japanese outfielder known as “Sugimoto.” However, shortly after Sugimoto’s arrival at spring training, discussions in the press about enforcing the color line surface. In response, Sugimoto chose to leave the tryout of his own accord.

1895

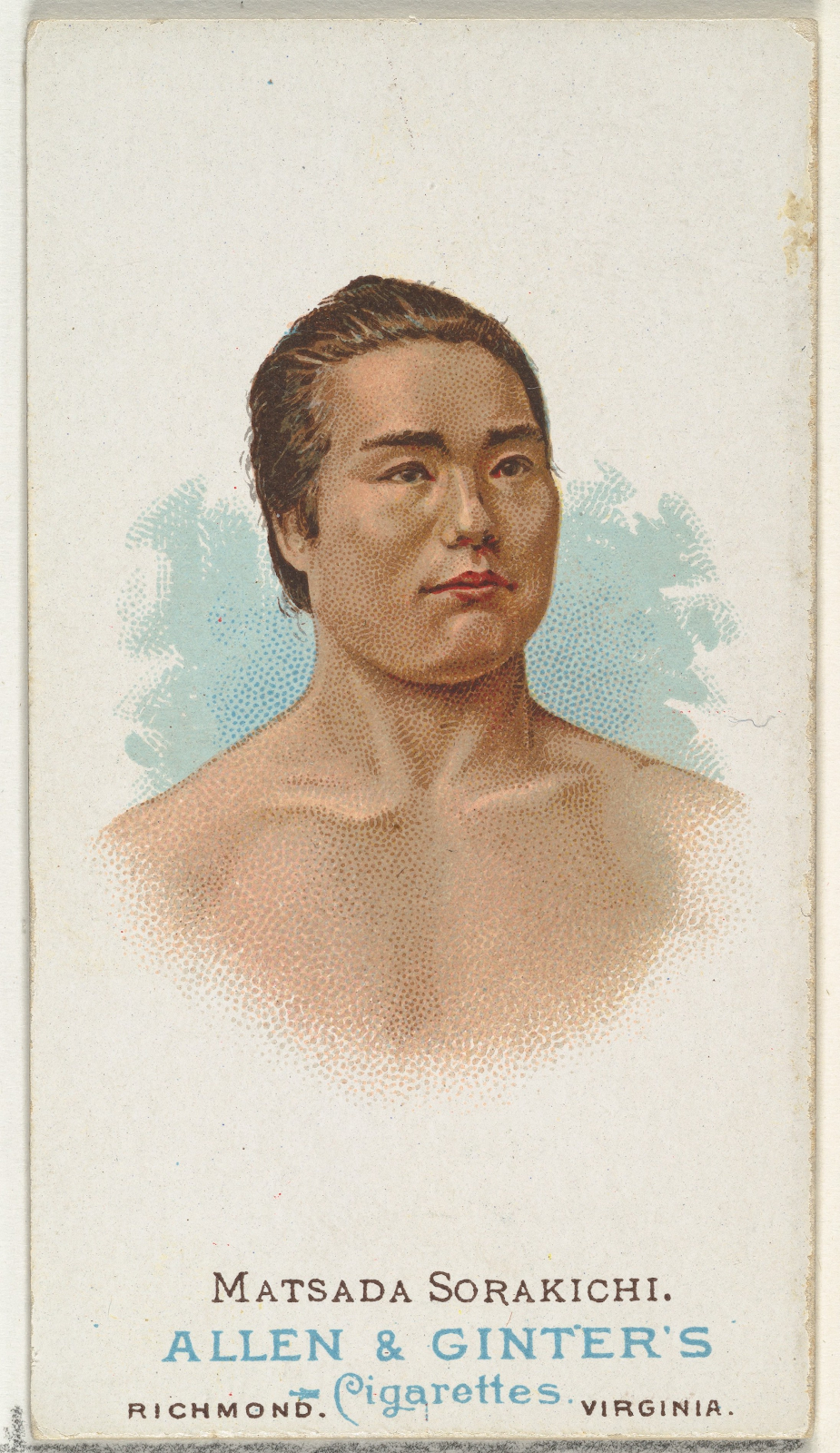

Dunham White Stevens, the American Secretary of the Japanese Legation in Washington, was described as “a baseball crank” and persuaded Japanese Minister Shinichiro Kurino to join him at several games. This gesture reflected one of the earliest examples of diplomatic engagement through sport. Meanwhile, Japanese American ballplayers were competing in amateur leagues in Chicago, and by 1897, a promising outfielder—identified in the press only as the cousin of wrestler Sorikichi Matsuda—was reportedly scouted by Patsy Tebeau, manager of the major league Cleveland Spiders.

1885

Sankichi Akamoto, a young Japanese acrobat and baseball enthusiast, played the game in America, blending cultural performance with sport. His presence foreshadowed the dual role many Japanese athletes would later assume—as both competitors and cultural ambassadors. Around the same time, at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, Japanese student Aisuke Kabayama competed on the school’s tennis and baseball clubs, eventually earning a spot on the varsity baseball team the following season. His participation is believed to be the earliest recorded instance of a Japanese-born player in U.S. college baseball.

1875

The seeds of Japanese baseball began to take root in the early 1870s, as people of Japanese ancestry played the game on both sides of the Pacific. In 1873, Albert G. Bates, an American teacher in Tokyo, organized what's considered the first formal school-level baseball game in Japan. According to Japanese sports historian Ikuo Abe, the game occurred on the grounds of the Zojiji Temple in Tokyo (image below). Tragically, in early 1875, Bates died at just 20 years old from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning while visiting a public bathhouse.

Image: "View of Zōjōji Temple at Shiba," by Yorozuya Kichibei (1790-1848), Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Image: Excerpt from Ikuo Abe's 2006 article "Muscular Christianity in Japan:

Image: Excerpt from Ikuo Abe's 2006 article "Muscular Christianity in Japan: The Growth of a Hybrid" in The International Journal of the History of Sport.

##